- Foreword

- Introduction

- The dubious modem dogma of the normality of homosexuality

- Homosexuality as a "Disease" of Self-Pity, A Neurosis

- History of the Self-Pity Theory for Homosexuality

- Part I: Generalities on Homosexuality; the Self-pity

- 1. Definition of Homosexuality; Latent Homosexuality, the Theory of a Bisexual Disposition, and the third Sex

- 2. Hormonal and Genetic Factors; Homosexuality as a Cultural Phenomenon

- 3. The "Self-Pitving Child" in the Neurotic; the Autopsychodrama, its Ongin and Fixation

- 4. Four Laws of Neurotic Complaining

- 5. Four Types of Justifications of Neurotic Complaining

- 6. Common Behaviors of the Complaining Compulsion

- 7. The "Child in Totum"

- 8. The "Child in Totum" (continuation)

- 9. The "Child in Totum": Common Reactive Behaviors (1)

- 10. The "Child in Totum": Common Reactive Behaviors (2)

- Part II: Male Homosexuality

- 11. The Autopsychodrama of the Male Homosexual

- 12. Some Elucidations of the Homosexual Autopsychodrama in the Male: The Preferred Partner

- 13. The Boy Who Does Not Belong to the Boyhood Community

- 14. Characteristics of Mothers and Characteristics of Homosexual Sons

- 15. Intermezzo: Effeminacy and Pseudofemininity in Male Homosexuals

- 16. Fathers of Male Homosexuals

- 17. Parental Attitudes as Catalyzing Factors; Additional Remarks

- 18. Other Catalyzing Factors for the Self-Image of "Being Weak, Unmanly"

- 19. Homosexuality-Related Complaints (1): Not Being Able To Face Life, Anxiety, Hypochondriac and Obsessive-Compulsive Complaints

- 20. Homosexuality-Related Complaints (2): Loneliness, Depression, Restlessness, Jealousy

- 21. Homosexuality-Related Infantile Attitudes

- 22. Dreams of Homosexuals

- 23. Bisexuality; the Married Homosexual

- 24. On Transsexualism and Transvestitism

- 25. Homosexual Pedophilia

- Appendix A. Other Variants of the Unmanliness Complex: Impotence, Don Tuanism, Sadomasochism

- Appendix B. Neuroticism (Neurosis-) Tests and Male Homosexuality

- Part III: Lesbianism

- 26. The Complaint of Being Inferior as a Woman

- 27. Lesbianism: Predisposing Factors in Childhood

- Appendix C. Neuroticism Tests and Lesbianism

- Part IV: Anticomplaining Therapy of Homosexuality

- 28. The possibility of a "Cure" of Homosexuality and the Nature of a Cure or Change

- 29. Nontherapeutically Cured Cases of Homosexuality

- 30. The Procedures of Anticomplaining Therapy: Self-Observation and Self-Analysis

- 31. Observation of the "Complaining Child" (Continuation)

- 32. Procedures of Anticomplaining Therapy: Analysis of the Individual "Child"; the Therapist's Observations

- 33. The Will to Change

- 34. Procedures of Anticomplaining Therapy: Techniques of Humor, Hyperdramatization

- 35. The Rationale of Humor Therapy

- 36. Hyperdramatization: Examples

- 37. Hyperdramatization: Variants

- 38. Hyperdramatization: Difficulties and Resistances

- 39. The Change

- 40. Results with Anticomplaining Therapy

- Appendix D. Notes on the Psychophysiology of Human Sexual Development

- Part V: Prevention of Homosexuality

- 41. How To Avoid Homosexual Development in a Young Child

- Bibliography

- About the Author

A Psychoanalytic Reinterpretation

Foreword

by Charles W. Socarides, M.D., Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City; Author of The Overt Homosexual (1968) and Homosexuality (1978)

Dr van den Aardweg has written an important and highly valuable book on the topic of homosexuality. It is a significant achievement of theoretical and clinical research and represents many years of study and devotion to unlocking the mysteries of causation of this serious disorder which has long been considered highly resistant to therapeutic efforts He provides us with a vast amount of information with regard to homosexuality as well as information of the furthest advances in the direction of therapy and ultimate prophylaxis of this condition His approach has been most careful and his extensive clinical experience and observations are both fascinating and definitive.

His approach is highly original. A childhood reaction of self-pity (self-dramatization, as he terms it) and the important role of this emotion in the adult psyche of the homosexual is a central part of his thesis. By self-pity (and its concomitant drive to complain) he does not mean purposive self-pity but «an addiction to self-pity» that is not conscious to the homosexual himself. What is said here about self-pity is new and deserves our interest; it does not necessarily collide with the position of other theorists on homosexuality, especially with insights made by Adler, Homey, Bergler, and other psychoanalysts. He describes the immaturity of a part of the emotional life of the homosexual — that is, they remain «children» or «adolescents» — and uses highly innovative therapeutic approaches: the use of self-humor (the exaggeration or hyperdramatization technique) in an effort to make a corrective self-insight in the patient. This can be of interest to therapists of many theoretical orientations.

This book is directed to anyone who is after knowledge and information concerning homosexuals. It provides extensive information on the specific childhood circumstances, parental relationships, and peer relationships that form the experiential substructure for the development toward homosexuality. He has compiled research data from different countries and offers a unique compilation of studies on the relationship between homosexuality and neurosis («neuroticism») tests.

Dr. van den Aardweg is to be highly commended for his courage in producing this extensive volume, for there are many today who tend to normalize what is essentially a severe psychosexual disorder (in its obligatory form) and many others who, for reasons of their own, would deny to the public and to behavioral scientists the information which this volume contains. The author is convinced that knowledge is a necessary condition for helping the troubled homosexual as well as for a sound public attitude toward homosexuals. Such scientific knowledge can only lead both to realistic laws and prevention of homosexuality. One-sided normalizing or moralizing propaganda does not help those troubled by deep homosexual needs. While homosexuality should be decriminalized, an action which all enlightened psychiatrists and psychologists approve of, it should not be raised to the level of «sexual naturalness.»

Dr van den Aardweg’s book is really a plea for help for the individual homosexual who has to cope with what an unfortunate childhood upbringing has so cruelly forced upon him. Homosexuals can only feel despair that psychology and psychiatry have forsaken them were it not for volumes similar to Dr. van den Aardweg’s. The psychological and psychi atnc nonsense and social recklessness of «normalization» may well bring social and individual tragedy. There may well be a rise in homosexuality of the nonobligatory type at first, but ultimately profound gender identity disturbances may increase and more true homosexual deviations will result as parents distort the maleness and femaleness of their infants and children. Homosexuals in therapy would develop resistances to therapy, retarding their progress, while others may be unwisely dissuaded from seeking appropriate help at necessary times. Suicides may well increase among persons with gender-identity confusion. Other medical specialists such as pediatricians and internists are becoming baffled by psychiatry and psychology’s faulty reasoning in declaring this severe psychosexual disorder nothing but an «alternative lifestyle.» Young men and women with relatively minor sexual fears will be led with equanimity by psychologists, psychiatrists, and nonmedical counselors into a self-despising pattern and lifestyle. Adolescents, nearly all of whom experience some degree of uncertainty as to sexual identity, will be discouraged from assuming that one form of gender identity is preferable to another. Those persons who already have a homosexual problem are discouraged from finding their way out of a self-destructive fantasy, discouraged from all those other often painful but necessary courses that allow all of us to function as reasonable and participating individuals in a cooperative society. Anyone whose task is the alleviation of distress in man (as is Dr. van den Aardweg) can only be saddened by the scientific unreason that has brought this to pass. Scientific research such as that presented in Dr. van den Aardweg’s important volume can only be applauded and encouraged.

Introduction

The dubious modem dogma of the normality of homosexuality

More than ever before, homosexuality is nowadays depicted as a normal variant of human sexuality. At least one in every twenty persons is declared to be homosexual, so that this variant would be everything but exceptional. This enormous group has been repressed and discriminated against for many centuries, chiefly on the basis of Christian prejudices, we are told. What should be changed, accordingly, is the negative attitude of society toward homosexuality and homosexuals; homosexuals themselves should be taught to fully accept their condition and be given the opportunity to live according to their «nature» without inner inhibitions or social restrictions. Exactly the same rights and facilities should be granted them as traditionally were the privilege of married heterosexuals.

If the basic supposition of the advocates of the homosexual emancipation movement is right and homosexuality would indeed be one of the natural variants of sexuality, one would have to agree with their striving to deeply modify what would then be the prejudices of our society. But what evidence can the spokesman of this theory produce to strengthen his point? He who will give the subject only a little thought will quickly realize how thin the ice actually is on which the homosexuality-is-normal theorist walks. Is it really so probable that nature created this normal variant which has no procreational potentialities but still possesses the anatomical and physiological apparatus for it? To what end would that serve? Does exclusive homosexuality as we know it in humans also occur in five percent of animals in their natural habitat? If normal or natural, why do heterosexuals not feel homosexual desires? In other words, one who believes that homosexuality is something natural or normal must present very strong arguments because everyone can see at first glance that the biology of man and animal alike does not favor that idea. Detailed study of the argumentation put forward by normality advocates (Chapters 1 and 2) will confirm this initial skepticism. Their opinion will appear not to be supported by anything resembling convincing factual evidence. At best, these theorists clutch at some straws of evidence which upon closer examination do not hold up. Having neither the arguments of logic nor the outcome of research on their side, they betray that their motivation is emotional, not rational.

This is understandable if one realizes that the first and foremost articulate defenders of normality theory were themselves homosexuals. As much as a century ago the Hungarian homosexual doctor Benkert pled for recognition of this sexuality. Oscar Wilde defended his homosexual love affairs in court, and in the years after the First World War, France witnessed the discussion between novelist André Gide and his adversaries on the normalcy of homosexual love for children. However, in the wake of the sexual revolution of the 1960s the homosexual emancipatory movement gained momentum and homosexuals came out, militantly proclaiming their full equality to heterosexuals. They met with growing support from all levels of society: politicians, journalists, physicians, psychologists, social workers, and the clergy.

The emotional motives of the homosexual himself may well be comprehended. He experiences his erotic striving as if it were instinctual and irresistible, as the expression of his intrinsic «natural self»; moreover, he often feels as if his happiness would depend on its satisfaction. His emotions, however, blind him to reason. He gives the impression that he cannot tolerate even considering the idea that his inclinations would be unnatural because in that case his whole life appears to him to be at stake. He tries to justify his way of life in whatever manner he can, although it is questionable whether he succeeds in completely convincing himself of his deepest feelings. In his neurotic egocenteredness he may project his feelings in others and may believe that they must have the same inner life that he has. Therefore, he may believe in the bisexuality of others. I think the constant preoccupation of homosexuals with their homosexuality as well as their attempts at proving that everybody is basically like them reveals their inner insecurity as to their normalcy. According to some of them, almost every celebrity in history has been a homosexual: Shakespeare would have been one, the Biblical figures of David and St. John, and the last few Popes. The implicit message is: «There is nothing abnormal in it; yeah, homosexual love is an even superior form of love, so that if you would draw the correct conclusion you would see that homosexuals are not inferior but privileged.» An example of glorification of pedophilehomosexuality was Gide’s booklet «Corydon» (1924) in which a physician eruditely teaches and exalts the incomparable purity and naturalness of homosexual pedophile love.

The militant homosexual mostly does not really listen to arguments and observations that contradict his normalcy view. Nor is he prepared to consider the opportunities for a change of his orientation unless in order to ironize them. The sheer existence of change possibilities would cast doubts on his position and therefore he tends to deny them, or takes a sarcastic attitude about the mere idea. Sometimes he dramatically criticizes attempts at modification as «expressions of fascistoid thinking» or nazibehavior. By preference he presents himself as the victim of social discrimination and he compares himself with Jews and Blacks; anyone who cannot consent to his views of normality runs the risk of being accused of discriminatory tendencies, of being «heartless,» «not compassionate,» and «old-fashioned.»

Doubtless, many homosexuals suffer from social contempt. More especially homosexual men whose behavior — gestures, movements, voice — is markedly effeminate can become the object of ridicule. (I have not in mind the affected, exhibitionistic effeminates, but those who make an effeminate impression without purpose and even against their will.) It is also true that many homosexuals, among them many who do not engage in homosexual contacts and are not happy at all with their condition, do suffer from the fear[1] that their feelings would be discovered, because they are afraid people would not accept them if they knew «it.» These facts, however, are often overdramatized by the ones who want full recognition for homosexuality and who like to invoke the image of the cruelly persecuted homosexual in order to silence every objection to their philosophy. They forget, for instance, that there are also homosexuals who never feel persecuted or discriminated against even if they openly live a homosexual life. They forget, too, that there are homosexual men who behave affectedly like pseudowomen on purpose, who like to shock, to provoke resistances, and who stir justified irritations.

They forget, moreover, that there are homosexuals who put the blame of all their misfortunes and personal failures on their position as the discriminated ones. That way, «discrimination» becomes a cheap slogan that obscures the real questions about homosexuality and hinders unbiased thinking (as far as we are capable of that) on such fundamental issues as: «Is homosexuality really normal?» and «What would be a responsible attitude toward homosexuality and homosexuals?»

It is clear that the defensive homosexual who tries to justify his ways cannot be the best evaluator of his own case. Still not a few of the most articulate publicists of the normalcy idea belong to this category: writers, physicians, psychiatrists, and psychologists. How is it possible that their claims have met with so vast a support from the educated community? As is known, the American Psychiatric Association decided in 1973 to cancel their former definition of homosexuality as an «emotional disorder.» It became a «condition» since then, but what is meant by that? Naturally this has been reinterpreted by the «normalists» in the sense that one would henceforward have to consider homosexuality as no longer pathological — and the APA set the example.[2] Politicians have joined the gay movement as well as various Councils of Churches; for instance, the Dutch Reformed Church practically declared homosexuality as normal. (For a matter-of-fact documentation of the «homosexual network» in American public life and politics, the reader must peruse the book of Rueda, 1982.) Europe and the United States disseminate their ideas, and are looked up to by less developed countries as being more progressive. So an intellectual and artistic elite has started the struggle for recognition of homosexuality «against prejudices» in Brazil; Colombia, which has had its liberation movement since 1977; but also in East Germany, where the homosexual emancipation movement is on the move within certain Churches. Obviously, something in the «spirit of the time» (Zeitgeist) favors this development that is not rational in essence. It has become a sign of humanitarianism to fight for liberation from whatever «taboos» and restrictions; for whole groups this has even become a new morality. The fact remains, however, that these movements and emotional climates are unscientific and threaten a more logical approach.

So the normality ideology has become prevalent in large sectors of the present intellectual and semi-intellectual society. It is considered «progressive» and «modern.» In Holland, for instance, it is the established philosophy of the majority of social scientists, university students, and social workers; and the media massively profess it. Nevertheless, it is not as certain that the public at large adheres to it. A questionnaire in this country revealed that, in spite of many years of propaganda, about 70 percent of the respondents believed homosexuality to be a sickness or disturbance (Meilof-Oonk et al., 1969). It is indeed most unlikely that the majority of ordinary people can be brought so far that they will regard homosexuality eventually as normal; a high degree of intolerance — or indifference, or apathy — may exist, but it seems illusory to suppose that most parents will ever become so permissive that it would barely interest them which direction the sexual development of their children would take. For all its impact on present day society, the idea of its normality will probably remain the wisdom of a relatively restricted intellectual elite. The largest Christian Church, the Roman Catholic, for instance, disapproves of homosexual behavior as contra naturam («against nature,» Declaration of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, 1975); in spite of protests by some groups of priests all recent evidence indicates that the doctrines with respect to this are not liable for change. Quite unexpectedly for many who read this, for sure, many psychiatrists today do not agree with the normality view. A questionnaire among a large sample of American psychiatrists disclosed that around 70 percent envisages homosexuality as a «pathological adaptation, as opposed to a normal variation» (Time, 1978). Note the striking similarity with the 70 percent of Dutch interviewees — ordinary citizens — in the investigation cited above. We conclude that there is a wide gap between the feeling of the «silent majority» and that of an active and influential minority whose voice is heard so frequently that it may falsely have been taken to represent the opinion of the masses.

And the homosexuals themselves? It is risky to estimate to what degree they subscribe to the ideology of the gay movement. Anyhow, many of them would rather change (if that were possible) than live as homosexuals, for a variety of motives: Social disapproval (the weakest motive), the wish to have a family of their own, the experience of the instability of homosexual relationships, inner rejection of the homosexual way of life on religious grounds or on the commonsense intuition that it is not normal, fear of AIDS. These persons are not helped at all by the seemingly ubiquitous recommendation that they had better fully accept their condition and live according to it. They feel put off by such easy solutions and in fact they are. If no other reasons would exist, solely the needs of these people would oblige (social) scientists to search for the causes and develop remedies.

Homosexuality as a «Disease» of Self-Pity, A Neurosis

In this book I shall make two main points. First, that homosexuals suffer from what may be designated as «neurotic self-pity.» The homosexual feeling itself will prove to be intrinsically related to self-pity. Second, that the treatment which is directed at the elimination of neurotic self-pity — so-called anticomplaining therapy — has essentially improved our therapeutic armament for this condition.

These are in fact two separate topics. A new insight into the causes and structure of a pathological condition of course does not automatically guarantee the effectiveness of a therapeutic method based on it. However, new insights can open up new ways of thinking in the field of therapy. They are no luxury if we evaluate our present therapeutic achievements with a bit of healthy self-criticism. There is much truth in the statement once made by Czech sexologist Nedoma (1951): «As long as we do not know its cause [of homosexuality], our treatment is bound to be mere groping in the dark.» With the identification of self-pity as perhaps one of the prime causes of homosexuality, treatment has become more goal-directed.

The method of coping with pathogenic self-pity proposed here is not offered as the only one imaginable. It is, however, original in that it exploits the curative value of humor and self-humor in order to overcome neurotic self-pity. A therapeutic technique like «hyperdramatization,» which I shall discuss in the section on therapy, deserves the attention of psychotherapists of divergent theoretical orientation.

The theory that homosexuality is caused by attachment to childhood self-pity (compulsive self-pity, or a compulsion to complain) should not be misunderstood. It is not flattering for anyone to be depicted as suffering from self-pity and in the light of current emphasis on the discriminated position of the homosexual a superficial reader might easily misinterpret this view as just another attempt to stigmatize and reinforce negative social prejudices. It is true that self-pity is not a beautiful or desirable emotion; however, the person with this emotion does not consciously or purposefully cultivate it, but rather is compelled to have it, against his own will. Therefore, it is a «disease» from which he suffers, although not a disease in the physical sense.

However, the homosexual who wants to stick to his normality conviction is not likely to accept the idea of being diseased by compulsive, involuntary self-pity either, because in the words of the philosopher Fichte «the head does not allow to enter what the heart does not want to.» I even think that if it were in the power of the militant homosexuals, the divulgence of ideas such as these, which are contrary to what they want to hear, would be interdicted. On the other hand, I have noticed many times that homosexuals who cannot be happy with their plight and who seek advice that is different from the usual «Accept it,» are not irremediably hurt to learn the diagnosis of self-pity but rather find support by every progress in self-insight. Furthermore, spreading of the insight of homosexuality as a self-pity «disease» will help the public take a more realistic and responsible attitude toward the phenomenon itself and toward the suffering from it. There is a list of old and a list of new prejudices on homosexuality which must be removed. On the one hand, homosexuals are often not understood in their inner problems and social inhibitions. On the other, full recognition of homosexuality as something natural is erroneously confused with charity and compassion. The reaction of the one who has accepted the view of this book will hopefully be comparable to that of a parent to a difficult child: He will not reject, but cannot and does not accept all of the child’s emotional expressions. He will try to understand what is realistic to understand, without becoming oversentimental. Without declaring healthy what is not, he will encourage attempts at betterment. By the way, this is the same attitude we try to take to every neurotically afflicted person.

The word «disease» I used to describe the compulsive character of self-pity in homosexuals should not give rise to misunderstanding either. Normally, this word is used for physical disturbances and for mental disorders with a probable physical cause. However, it is appropriate to emotional disturbances with psychic causes as well. Also in these cases we encounter two essential elements of what we are used to call «disease,» viz., inadequate or abnormal functioning of some part of the body or mind, and the fact that the person is submitted to the condition without his will or responsibility. In a similar sense the word «sick» is used, denoting both physical and psychic imbalances.

We may, as a matter of fact, substitute «neurosis» for the description of «disease» of self-pity. Homosexuality in this book is conceived of as a variation of the broad category of neurosis. Properly speaking, the term «homosexuality» is somewhat deceptive because it only refers to the most salient symptom of what in fact is a generalized emotional imbalance. Many people have neurotic inclinations, grave or mild, and the similarity between homosexuals and other neurotics is greater than their difference. Homosexuals have the central pathological mechanism of compulsive self-pity in common with anxiety neurotics (phobics), neurotic depressives, obsessive-compulsive neurotics, and many others suffering from organic and neurosoma tic ailments.

A frequent objection to any homosexuality theory that links the condition to neurosis is that such a theory is based on a biased sample of people, clients, or patients. Psychotherapists would usually see the neurotic homosexual so that their view would be seriously distorted. This sounds, however, too much like a priori reasoning. As far as the self-pity theory is concerned, it is true that it has been developed from observations collected during the psychological analyses of persons who wanted to change their sexual orientation, or who otherwise had emotional problems, but must such a wish in itself be uniformly interpreted as an indication of neurosis? Indeed, groups of homosexuals differ one from another in sociological as well as psychological variables like IQ, level of education, and job satisfaction, due to the manner in which they are selected. But the supposed difference in neurotic emotionality between homosexuals who visit a therapist and so-called nonclinical homosexuals has not been confirmed by research with psychological tests measuring neuroticism (see Appendix B). Otherwise, the existence of the self-pity mechanism has been checked in many homosexuals who did not want to change, both within and without the psychological consulting room. I feel confident, therefore, that this theory applies to homosexuals in general, that it is generalizeable, that the self-pity compulsion will be found in homosexuals of varying psychological and sociological or cultural backgrounds.

We must also turn down the objection that the self-pity observed in homosexuals would be the result of social discrimination. It proves to be an autonomous psychic force which functions in large part independently of the person’s life situation and which is the cause of the homosexual orientation itself, not the effect of the homosexual’s difficulties in social life, however real that additional suffering may be.

That homosexuality is a «sickness» does not mean that the entire emotional life of this person would be sick or neurotic. I shall sharply distinguish between the normal, adult part of the homosexual’s personality and the inner structure of autonomous self-pity which actually is described as an infantile ego. This book will focus on the infantile part of the emotional life, the source of the disease, but the reader should not lose sight of the fact that we regard it as an intrusion in an otherwise more-orless-normal mind. The homosexual possesses a double personality.

History of the Self-Pity Theory for Homosexuality

The present theory did not arise all of a sudden but is the outcome of a gradual evolution of insights in neurosis and homosexuality, acquired by psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapists. Its founder, Dutch psychiatrist Johan Leonard Arndt (1892–1965) has integrated a wide variety of observations and insights of former theorists, notably of Alfred Adler, and of his own teacher, the Viennese psychiatrist Wilhelm Stekel. The latter, one of Freud’s first disciples in the psychiatric world (and a later dissident), had accepted the observations of his great master on homosexuality but added to them some of his own, elaborating a somewhat differing theory of its origin and psychodynamics in his books Masturbation and Homosexuality (Onanie und Homosexualität, 1921) and. Psychosexual Infantilism (Psychosexueller Infantilismus, 1922). Confirming Freud’s ideas on the psychodynamic origin of homosexuality in childhood, Stekel minimized the importance of a supposed hereditary predisposition much more than Freud and was perhaps the first to classify it as a neurosis. Moreover, he disagreed with Freud on the causal role of the famous Oedipus complex but pointed to a number of failures in the upbringing of the child which could bring about the disorder. More than Freud, he believed in the possibility of a radical change of this orientation, though he, too, thought it would occur relatively rarely. His various observations deeply influenced the thinking of his pupils. In a sense, it can be said that Arndt, who was trained by him in the years 1934 — 36, has elaborated and completed several Stekelian observations and intuitions like the following: «He [the homosexual] is the unhappy one, who feels condemned to suffering by his fate!» or «I have never seen a healthy nor a happy homosexual,» or «[He is] an eternal child . . . who struggles with the adult» (Stekel, 1921). With his introduction of the self-pity principle, Arndt did not cancel in any way the observations of his predecessors but united them in a synthesis which also accounts for a great many relevant observational data gathered by authors of various theoretical schools. The homosexual, he said, is possessed of an internal structure which behaves autonomously as an infantile ego, a child who is compelled to indulge in self-pity. Having discovered this mechanism first in some cases of neurosis with a nonsexual symptomatology (Arndt, 1950), he gradually became convinced of its occurrence in neurotic persons of many varieties and finally recognized it in homosexuals as well (Arndt, 1961).[3]

Next to Stekel, Arndt’s thinking was influenced by Adler. Also Adler had long ago emphasized the psychological origin of homosexuality in his essay «The Problem of Homosexuality» («Das Problem der Homosexualität, 1917); he had asserted, moreover, that from his experience the homosexual man possesses an «inferiority complex» in relation to his masculinity. In fact, the self-pity theory fully accepts and incorporates this notion. Otherwise, the student of Adler’s descriptions of the emotional attitude to life of the neurotic personality, with its typical lack of firmness and courage, will be struck by its similarity to Arndt’s notion of self-pity. (For an excellent introduction to the ideas of Adler we may refer to Schaffer, 1976.)

In the past decades, various eminent psychotherapists have investigated homosexuality from a psychodynamic point of view. Their observations and many of their theoretical conceptions are highly valuable contributions which are not refuted but gratefully accepted by the present view. Notably, I think of the works of Marcel Eck (1966) in France and of the psychoanalytic studies of Bergler (1957) and Socarides (1968) in the United States, and I mention especially the book of Hatterer (1970). Hatterer does not construct a theory but pragmatically describes a procedure for treating the homosexual man. The descriptions he gives of behavioral and emotional reactions of his homosexual clients as well as his observations on many phenomena encountered in the course of therapy are very worthwhile and fit in well with the framework of self-pity theory (cf. his observations on inferiority feelings, idolization of the homosexual partner, the tendency to feel a victim, etc.). As to Socarides (1968, 1978), his reflections on the homosexual’s gender identity are much akin to the concept of gender inferiority feelings as used here.

The present book is the result of more than twenty years of theoretical study and of the treatment of about 200 homosexual men and 25 lesbian women from the viewpoint of self-pity theory.[4] In my opinion, this theory is more than just a new synthesis of old things, but an improvement on our knowledge. I trust it will be carefully examined by those who wish to understand homosexuality theoretically and by those who want to help the afflicted and seeking homosexual to become emotionally more mature.

Part I: Generalities on Homosexuality; the Self-pity

1. Definition of Homosexuality; Latent Homosexuality, the Theory of a Bisexual Disposition, and the third Sex

Not all sexual contacts or manipulations with members of the same sex need be homosexual in the proper sense of the term; boys may have incidental contacts of mutual masturbation with other boys, or people in some non-Western cultures may have sexual contacts with members of their own sex for ritual or other reasons, without those behaviors having the characteristics of real homosexual motivation. We shall reserve the word homosexual (homophile) here for erotic wishes directed to members of the same sex (1), accompanied by a reduction of erotic interests in the opposite sex (2). Then, we have to distinguish between transitory homosexuality, which may be a phase of development, especially during adolescence, and chronic homosexuality, the latter being the type of homosexuality that is generally meant when one uses the term. According to this definition, the criterion lies in one’s feelings, not in one’s manifest behavior. There are persons with clear homosexual tendencies who will never express them in their sexual behavior, whereas other persons may engage in homosexual contacts without a real homosexual motivation. The latter type of homosexual behavior is not preponderant in our culture, although there are unstable personalities who lend themselves to sexual contacts with real homosexuals, in exchange for money. Moreover, confused by the type of propaganda that paints homosexuality as just another possibility of sexual gratification, there are youngsters who think it is interesting to «experiment» with this «variety.»

Further, our definition covers all grades of intensity of homosexuality. Even a transitory period of erotic attraction to someone of the same sex has to be viewed as a manifestation of real homosexuality, albeit of a mild degree. The description that will be given henceforth as to the psychic dynamics of homosexuality does hold even in the mildest cases of homosexual wishes (which are accompanied by a reduction in heterosexual interest). For this reason, it would be correct to use the term «homophilia,» with its stress on the subjective feelings of the person («philein» — Greek for «to love»). Although we shall take up this logically superior term now and then in the present study, we shall not prefer it consequently, because the word «homosexuality» is too common to neglect.

Our definition does not make a distinction between such concepts as «nuclear» and «peripheral» homosexuality. I do not believe that this distinction makes very much sense. There are homosexuals who are entirely homosexual in their erotic feelings, and scarcely heterosexual, and there are homosexuals who have, alternately, phases of homosexual and heterosexual interests. This is, in fact, only a question of degree and not of qualitative difference. The longitudinal picture of homosexual impulses in one person may show shifts as to the prevalence of homoand heteroerotic interests, or oscillations in the strength of homosexual preoccupations. There are many degrees of intensity, as well as many variants of homosexuality: One homosexual prefers partners of his own age, another of a younger age, still another is attracted to partners of several ages. (Homosexual pedophilia is included in our definition.) There are homosexuals who prefer a circumscribed type of partner — with respect to physique or demeanor — while others have several preferred partner types or even seek somewhat indiscriminately all males of a certain age range. There are homosexuals who look for many contacts, while others intend to establish a more stable relationship with one partner only (regardless of whether they really can maintain such a relationship). In some, the sexual urge is predominant while in others it may be a secondary element in their search for contact. Some male homosexuals are outspokenly feminine in appearance, while others cannot be discriminated from nonhomosexuals in their manners and general conduct; likewise, some lesbians manifestly behave in a masculine way while others are completely «feminine.» If we like, then, we can distinguish between homosexuals according to their preference of partner types, or according to the intensity of their sexual impulses, etc., but the dichotomy of nuclear versus peripheral homosexuals does not seem to be very useful. One may even become more skeptical with regard to this typology because with nuclear sometimes the suggestion is given of irreversibility, or unchangeability. I heard a psychiatrist saying in a television interview that «nuclear homosexuals are uncurable.» However, some moments later in the same conversation, he admitted that he «could not possibly tell which homosexual was a nuclear one,» clearly demonstrating the mystification surrounding the conception.

The notion of latent homosexuality is a different case. Some adults indeed do not recognize their homosexual interests for a long time, until they experience something emotional that opens their eyes to their inclinations. Many young people, in fact, only gradually become aware of their homoerotic orientation, passing through a phase which might be called a period of latency. «Being latent» should not be confused with «unconscious,» though. It means that the subject has a special, erotically colored interest in persons of the same sex but does not realize the nature of his feelings, as in the case of someone who feels inferior but cannot put his feelings into words. Consequently, a latent homosexual who will do some self-searching will generally be capable of discovering the meaning of interests and feelings he did not understand before. It is very possible that another person already surmised the homosexual inclination of the subject in question, for instance, noticing his way of looking at people of his own sex, or his way of talking about them, or his lack of interest in the opposite sex. Maybe this person draws the attention of the subject to the nature of his erotic interests, making him recognize what it is he actually feels, but this cannot be adequately described as «making conscious what was in the unconscious,» because having recognized the meaning of his feelings the latent homosexual may remark: «Yes, I always felt that way,» indicating that his feelings were not strictly unconscious before their meaning dawned upon him

I believe we have to reject this latency concept, according to which the person who is presumed to have homosexual impulses cannot perceive these feelings at all, because they would have been repressed to his unconscious. This kind of reasoning, which is not uncommon among some psychoanalysts, leads to uncontrollable and sometimes harmful assertions. For instance, a man with a neurotic compulsion of chasing women (a Don Juan) is sometimes considered a latent homosexual, whereas, in fact, he never experiences nor experienced the least erotic interest in men. It is true, however, that some homosexuals, who are, at least partially, aware of their homoerotic feelings, «chase» women in order to prove to themselves that they are not failures as a man, but in these cases we might use the term «pseudo-Don Juans,» because of the fact that they do not really care for women. Another observation in this context is that the type of inferiority complex encountered in the real «Don Juan» resembles the type of inferiority complex of homosexuals, in that it is also related to a negative self-image as to gender identity. The same is true, for many forms of sexual impotence in nonhomosexuals; these persons share feelings of inferiority with regard to their masculinity but do not suffer from homosexual strivings.

Bisexuality or ambisexuality is sometimes considered a distinct category. In reality, the majority of homosexuals indicate the awareness of at least some heterosexual feelings, though of low intensity and frequency. In my sample of about 200 homosexuals in treatment, for instance, about 70 percent thought, at the onset of treatment, that they had experienced some heterosexual sentiments. Possibly, a more accurate analysis of all sexual dreams and impulses during a long period will show an even higher percentage of rudimentary heterosexual feelings, confirming Freud’s impression that there were «blighted germs of heterosexuality» in all homosexuals (Freud, 1935). We seldom meet a homosexual with highly pronounced heterosexual feelings, whether he has heterosexual contacts or not, so that we agree with the statements of such researchers as Bergler (1957) and Freund (1963) that the homosexual motivation in socalled bisexuals is predominant. Westwood (1960), interviewing 127 socially well-adjusted English homosexuals, called 42 percent of them bisexuals according to the criterion of their having heterosexual contacts, but only 10 percent of these expressed their preference for a heterosexual partner (= 4.2 percent of the total group). So-called bisexuals, then, have always defective heterosexual tendencies, and their sexuality is not evenly divided into a homosexual and a heterosexual component. In line with this is the fact that about 60 percent of homosexuals in various samples refer to themselves as «exclusive homosexuals» (Bieber, 1962; Loney, 1972). This is not in discordance with our observation on the occurrence of rudimentary heterosexual impulses in about 70 percent of homosexuals analyzed at the onset of treatment: the majority of them would readily classify themselves as «exclusive homosexuals» on the Kinsey scale.[5]

According to some authors, including well-known psychoanalysts, every human being possesses an innate bisexual disposition. As they see it, cultural factors determine which side of this basic sexual disposition will be developed; our culture would favor a heterosexual development, suppressing the homosexual element, but in some cultures, or groups, or family constellations, it may be the reverse. I believe that such a theory is completely erroneous.

In the first place, if man really had as much erotic interest in his own as in the opposite sex, chances would have been 50-50 that he had repressed the heterosexual side of his sexuality in the course of evolution or development of history and culture, just as he would have repressed his homoerotic interest in our culture. In other words, if heterosexual interests would not be, innately, much stronger and compelling than the homosexual component, nature would have gambled with the survival of mankind, equipping man with a wonderfully functioning anatomical and physiological sexual apparatus, but leaving its final destiny in dependence on the vicissitudes of cultural and historical factors. Certainly, from the point of view of evolution — and of the principle of finality in nature in general — this would have been an «unnatural» risk. Secondly, this kind of equivalence in erotic interests is not encountered in the animal world where animals live in their natural habitat (Eibl Eibesfeldt, 1970). Heterosexual interest in animals prevails, and homosexual behavior has to be explained in function of other than strictly sexual drives (social dominance, or the neutralization of aggression: West, 1960; Eibl Eibesfeldt, 1970). Moreover, bisexuality in the form of equivalent erotic interests in both sexes is virtually nonexistent in the human person. In those few men or women with homosexual inclinations who may experience strong heterosexual feelings we never observe homoand heteroerotic wishes at the same time. They live alternately through periods of homosexual and heterosexual interests, and even in the latter their heterosexuality proves to be, on closer inspection, reduced in comparison with normal heterosexuality. For these reasons, the idea of an inborn ambisexuality is highly unlikely. For some authors it is a way of furnishing a theoretical basis for the defense of the acceptability of homosexuality. «The direction which is taken by the sexual instinct is a matter of relativity,» they argue, «and the fact that the great majority is heterosexually oriented is a product of chance, of culture; it could have been just as likely the other way around.» Some may add: «The heterosexual majority is as sick as the homosexual minority, because they repress their homosexual instinct,» or «Everybody is partly homosexual, and therefore, homosexuality is in no way exceptional.»

The great majority, however, is not bisexual; it is not very plausible that the homoerotic component would have been repressed in our culture, because many boys have homosexual contacts during some period of boyhood or adolescence but stop with them as soon as they discover the sexual possibilities of the opposite sex, without preserving homosexual longings afterwards. (See the observations of McCleary, 1972, on homosexual practices of ghetto boys, and Ramsey, 1943.) There is no reason at all to assume a process of repression involved in this shift of attention. Would their former «homosexuality» really have been so rewarding, we would expect them to continue with it, because social repression does not extinguish the lust for power or possessions: What is pleasurable has more power than punishment, or shame. On the other hand, the implication of the theory of ambisexuality, viz. that the homosexual, in his turn, repressed his heterosexual instinct, is not less improbable. Many homosexuals consciously try to feel heterosexually but do not succeed and simply conclude that they have no heteroerotic interest despite their efforts.

Naturally, we may accept a kind of «ambisexuality» in the sense of man’s possibilities to develop an erotic interest in the same sex during a certain phase of psychological development, i.e., during the phase of sexual immaturity. A child may feel erotic interest in members of his own sex during the period of the onset of his sexual development, when his sexual instincts have not yet fully unfolded, but precisely because this is only a stage of development, this will pass over in his psychological ripening, in a spontaneous and natural way. Explained in this manner, the concept of bisexuality loses its meaning, because it is as much true that a child and (pre-) adolescent may develop temporary erotic interests in younger children, or in nonhuman objects which suggest to him some sexual meaning, in his own body, and even in animals. Thus, we had better change the term «bisexuality» for Freud’s «pansexuality» and assert that, as a transitory stage of psychosexual development, the human person is «polymorphously perverse» (Freud, 1938), although the qualification is not very recommendable because of its heavy pathological connotations. Later in this book I shall elaborate on the development of the human sexual instinct, but here I want to stress that the development of erotic wishes is inevitably in the direction of the opposite sex, so that the psychologically and biologically mature person will exclusively feel heterosexual interests.

Even more peculiar is the opinion that homosexuals would constitute a «third sex,» often thought of as intermediate between men and women. Sometimes, homosexuals themselves adhere to this kind of theory of an «intersex» (Magnus Hirschfeld, 1953); if they would think a little more about such a theory, however, its supporters would have to conclude that more than one intersex must exist: At least two of them, a male and a female variant for male and female homosexuality, respectively. Further, a third type of intersex should be postulated for male homosexual pedophilia (the male homosexual pedophiliac generally does not have sexual interests in adult men, only in boys before the age of adolescence), and a fourth for female homosexual pedophilia. And what about the other sexual deviations, such as gerontophilia (sexual attraction to old people), fetishism, heterosexual pedophilia (sexual interest in children of the opposite sex), zoophilia (sexual interest in animals), necrophilia (erotic interest in dead human bodies)? Would it really be acceptable to assume the existence of such a variety of human beings, all of them being normal variants of mother nature? The answer, for everyone who uses his common sense or respects the principle of finality of biology or of selection of the most adapted forms of life according to the doctrine of evolution, cannot but be negative. Nature does not create different variants of a species which have no chances of survival, so they have to be regarded as either degenerations or normal creatures with some kind of illness or disturbance. Luckily, homosexuality does not prove to be the result of degeneration; it is a function disturbance in a basically normal individual.

2. Hormonal and Genetic Factors; Homosexuality as a Cultural Phenomenon

There are no indications of systematic differences in hormonal components between homosexuals and heterosexuals (Perloff, 1965). Some recent reports do mention differences in level or quality of metabolic products in the blood serum or urine of homosexual men, as compared with heterosexual controls, but these findings hardly support the theory of a biological or physical factor as the cause of homosexuality. For instance Kolodny et al. (1971) found lower testosterone levels in the blood plasma of a group of exclusive homosexuals as well as an impaired spermatogenesis (less spermatozoa in the semen and less motility of spermatozoa), in comparison with homosexuals who were not 100 percent homoerotic in their orientation as well as with heterosexual controls. The authors, however, are cautious in their conclusion «In fact there must be speculation that the depressed plasma testosterone levels could be the secondary result of a primary homosexual psychosocial orientation, with depressive reaction relayed through the hypothalamus from higher cortical centers» (p. 1173). We remember the studies quoted by Arieti (1974) on the relationship of amenorrhea and disturbances of the menstrual cycle in patients with schizophrenic episodes and also in neurotics. These data suggest that the emotions or the psychic attitude may inhibit the production of hormones, probably by mediation of the pituitary gland. By tradition, there is a tendency to identify too quickly some physical factor which has been found to relate to some psychological syndrome as its cause, whereas it might be as well, or even more likely, its consequence. The studies on physical correlates of schizophrenia warn us not to draw such a conclusion too hastily; sometimes a physiological or metabolic factor A or B is found to differentiate between a group of schizophrenics and controls,[6] but mostly subsequent or cross-validating investigations fail to repeat the original findings. In the case of the results of Kolodny et al., we have, at most, an interesting suggestion as to the inhibitory capacities of psychological factors on the processes of gender hormone production,[7] but it would be wise to hesitate to draw even this conclusion before further studies with other groups of homosexuals and controls will have corroborated the findings. For example, it could be as well that the results are artifacts of the feeding customs of these patients, and we should like to know too the possible influences on testosterone production and spermatogenesis of marihuana and barbiturates, since the authors remark that 43 percent of the homosexuals were regular users of marihuana (!) and 20 percent used barbiturates or amphetamines.[8]

The study of Evans (1972) might also be interpreted prematurely as a confirmation of some causal physical factor existing in at least some homosexuals. In fact, the author found little, if any, differences between homosexuals and controls in the quantity of androgene and estrogene end products in the urine, thus confirming earlier findings as to the normalcy of the composition of sex hormones in homosexuals. However, he demonstrated differences in the quantity of blood serum lipids and some other metabolic factors between homosexuals and controls, as well as in metabolites of adrenocortical hormone:. However, the homosexuals had a significant lower body weight, less muscular power (as measured on a dynanometer), and a lower level of creatinine (the end product of creatine, an index of muscle development). These results tilt the thinking of the investigator toward the acceptance of a factor of deficient muscle development which would probably be one of the causes of the sexual deviation itself — at least in some homosexuals. Thus, the physical characteristic underlying the development of male homosexuality would not be an attribute of the gender hormones (which, allegedly, are normal in homosexuals), but of muscularity and physical strength. The data of Evans deserve some comment, in view of the eagerness of some proponents of the «homosexuality is normal» philosophy to interpret any indication of a physical factor associated with homosexuality as evidence for a biological substrate to this orientation, with the implication that such a substrate would be inherited. Before definite conclusions can be drawn, however, one has to wait for validation of the Evans data in other homosexual groups (see our remarks concerning the findings of Kolodny et al.). If future investigations should bear out the existence of a type of homosexuality-associated physical factor as suggested by Evans, there still would be no compelling reason to see it as the cause. Possible anomalies in muscle development could as well be the basis of a self-view of being inferior which in its turn could start a sequence of psychological reactions ending up with homoerotic sentiments. Compare this course of events with the development of other inferiority complexes on the basis of some physical peculiarity. For instance, a child who is much smaller, or taller, etc., than other children may develop the self-image of inferiority by which he eventually may become neurotic; in these cases, not the physical factor of smallness can be considered as the cause of the neurosis, but the self-view subsequent to it. As a result, if a physical factor of a relatively underdeveloped musculature could be demonstrated in certain homosexuals it might be the basis of a self-view of being inferior with respect to body strength, eventually leading to homosexual interests. As we shall see afterwards, many homosexual men indeed viewed themselves as weaklings during childhood or adolescence. (By the way, it remains questionable whether this self-view indeed rested on an objective lack of physical strength.)

It is also conceivable that a factor like reduced bodyweight or deficient muscle development would be a consequence rather than a cause of homosexuality (in males) or of a specific self-view of inferiority. Somebody who has an inferiority complex relative to his body-strength is likely to avoid physical exercises, sports activities, and professions requiring physical effort. It is improbable that a habit of physical effort — by sport or labor — would not reflect in measures of muscle development and, therefore, one might suppose that people with little muscular training make deviating scores on tests of such a factor in comparison with people with more physical training. Moreover, the self-image and other psychological factors may profoundly influence a person’s nutritional habits. That a similar explanation of — not yet unequivocally established — metabolic characteristics in homosexual men is not too far-fetched may be obvious if one realizes that many homosexuals indeed demonstrate an attitude of physical passivity and dislike «manly,» assertive, and combative activities, more out of neurotic weakness or a lack of psychic firmness than as a result of a shortage of physical energy. Thus, in another article which deals with the same group mentioned above, Evans relates that the homosexuals frequently felt «weaklings» already in childhood and puberty (Evans, 1969). His results may have been influenced by the difference in age between the homosexuals and heterosexual controls, the latter being on the average 4.5 years older. As to the difference in body weight: One might invent several more explanations, among which the supposition that the married life of part of the heterosexuals, combined with their higher age, led to different feeding habits. Not infrequently, married men increase in weight after a few years.[9]

In view of its limited significance, we analyzed several aspects of the study of Evans perhaps too extensively — with the aim of demonstrating the restricted range of generalizations that can be drawn from this type of research. Too frequently one comes across unwarranted conclusions from a few, multi-interpretable differences between specific groups of homosexuals and heterosexual controls. To quote another example, too much has been made of the results of the East German group of Dörner (Dömer et al., 1975). He found a group of homosexual men to react more strongly to estrogen injection by an increase of initial LH values than a group of heterosexuals and bisexuals. Later, he reported lower «free» plasma testosterone concentrations for effeminate homosexuals; he launched the idea that they would have developed a feminine sexual brain due to androgen deficiency during a critical prenatal period (Dörner, 1976). Male homosexuals then would have a decreased level of «free» androgen and a higher estrogen level.

Some objections to this theory are that the critical period for the alleged androgen influence on the masculinization of the brain’s sexual response center only, with the exclusion of its influence on other sex-related brain centers, has not been demonstrated for humans. The androgen deficiency would not have worked in homosexual men on the development of their genitals, as they are fully normal in that respect (not to speak of lesbian women). The case for lesbians appears to be even more difficult, as it has been shown that women who were prenatally exposed to high androgen concentrations behaved more tomboyish than other girls (suggesting androgen influence on the formation of sex-linked behavior centers), without becoming, however, lesbian in sexual orientation (Ehrhardt, 1977). Also, one might expect the same hypothetical androgen deficiency in male animals — but male homosexuality in animals that is Strictly comparable to the human orientation does not exist.[10]

«There is a need to ask why a hormonal influence on sexual orientation is so difficult to discern in human beings. Is it because the endocrine influence is nonexistent or weak relative to social conditioning?» Goy and McEwen (1980) wonder in discussing a number of relevant physiological studies reported in a neuroscience work session in 1977. The most careful and defensible answer seems to be «nonexistent» indeed! Not only are the theoretical objections to an endocrine theory of homosexuality impressive, the reported hormonal differences between groups of homosexuals and controls on which such a theory must be based are in all likelihood either artifacts of the compositions of the groups under investigation, or they reflect effects of behavior (sexual and other) rather than causes. I already mentioned the observation of Rose et al. (1972) that social factors may influence the testosterone level in primates, but there are other possibilities for alternative explanations as well. That we have to think in this direction is strongly indicated by the failure of many investigators to repeat sometimes reported differences in hormonal levels between homosexuals and heterosexuals (for instance, Friedman et al., 1977; a series of studies to this effect may be found in Masters and Johnson, 1979). The conclusion of Perloff some twenty years ago, that no convincing demonstrations of endocrine causation of homosexuality have been forthcoming, still holds. We have no reason to assume abnormal hormonal developments or any other lack of physical masculinization (and feminization, respectively) in persons with homosexual interests.[11]

Homosexuality cannot be explained with a genetic theory either. For example, even men with a feminine type of sex chroma tine do not have abnormal sexual feelings, in contrast to the absence of this factor in a large homosexual sample (Raboch and Nedoma, 1958). Also, deductions from a genetic hypothesis such as that homosexuality would occur more frequently in some families than in others, or that male homosexuals would have more brothers than male heterosexuals (under the hypothesis that male homosexuals would possess recessive female genes) were generally not borne out, despite some earlier reports (Miller, 1958; West, 1960; Bieber et al., 1962; interestingly, in a reanalysis of the data of Bieber et al., Gundlach and Riess, 1967, found that male homosexuals had more sisters than brothers, whereas their own sample of lesbians had less brothers than controls, but not more sisters).[12]

Sometimes one hears the argument that the results of Kallmann’s homosexual twin research point to a genetic factor (Kallmann, 1952). He reports that 11.5 percent of the twin brothers of homosexuals who were members of dizygotic pairs rated themselves as «predominantly» or «exclusively» homosexual on the Kinsey-scale, whereas a group of homosexuals who were members of monozygotic twin pairs had a homosexual twin brother in 100 percent of the cases. The criteria for calling a monozygotic twin brother a homosexual, however, were less strict than those used for the dizygotics. Certainly this result is fascinating, although one need not see the necessity to interpret it in favor of a genetic theory. There are too many unknown variables involved. First, it is well-known that selection plays an important role in these studies of twin concordance. The investigator starts with those homosexuals of whom it is known that they are members of a twin pair; thus, he is likely to collect a biased sample. Further, we have to reckon with the effect in monozygotes to show themselves identical — it is really peculiar that Kallmann observed many of them to be similar even in small behaviors, in gestures and demeanors, which under the assumption of a hereditary factor, would imply that their behavior was genetically programmed into details, an inference that cannot be upheld unless we forget all we know about the influence of upbringing, self-image, and habit formation in childhood and adolescence. Apart from the often disputable classification «monozygotic» (sometimes containing a circular element: Those who resemble each other closely are called monozagotic twins»), the higher concordance between monozygotes might be well explained by a psychological theory which stresses the mutual identification of monozygotic twins.[13] Everybody knows of examples of supposedly monozygotic twins who live as each other’s duplicate, and thus it would be highly interesting to explore cases of homosexual monozygotes as to their whole psychobiography, their selfview in function of their vision of their twin counterpart, and their psychic reactions to childhood experiences.

Another argument for a psychological explanation of Kallmann’s findings is his 11.5 percent concordance in homosexuality between dizygotic twins. Considering that dizygotes do not differ more in genetical pattern than nontwin brothers this is quite a high percentage. Such high incidence of homosexuality in brothers of homosexuals was found in no investigation, so that we are led to the conclusion that nongenetic factors underlie this concordance. Eizygotic twins, too, are often educated equally, or treated as a pair, although to a smaller degree than monozygotes or children perceived as such. But, if we accept that equality of treatment and/or equality of self-perception cause the high concordance of homosexuality in dizygotic twins, why would the same factors not be responsible for the very high concordance in monozygotes? For the rest, Kallmann’s results are not generalizable. Too many cases of monozygotic pairs are known in which one member is a homosexual, the other definitely not. I have seen two such cases myself, and more are described by West (1960), Rainer et al. (1960), Klintworth (1962), and Friedman et al. (1976). Moreover, the latter authors did not find differences between the members of monozygotic twin pairs who were discordant in homosexuality on a series of biochemical and physiological tests, which indicates that these factors could not be held responsible for the homosexual tendency. Finally, it is interesting to learn that of all 121 pairs of identical twins who could be traced in Europe, the United States, and Japan, only one woman was known to be a homosexual and her sister not. One man accused his brother of homosexual inclinations toward him, but his brother’s alleged homosexual orientation could not be verified. It is possible that the total group consisted of some more, although not recognized, homosexuals, but the information is certainly not supportive of the «one in twenty» slogan (in fact, 1 or 2 out of 242 cases does not even make 1 percent). The case of the lesbian woman was clearly psychodynamic: she had a developmental history of a bad relationship with her stepmother and strongly identified with her stepfather (Farber, 1981).

Much has been made of the alleged high incidence of homosexuality in other than our Western culture, with the suggestion that our concepts or normality and abnormality in this respect are relative and would not reflect man’s «true» biological nature. Although homosexual acts between children, adolescents, and adults are rather usual in a number of nonWestern cultures (Ford, 1949), it is more than dubious whether one can call these behaviors «homosexual» in the sense of our definition, i.e., as expressions of homoerotic wishes. Also, in many cultures a kind of ritualistic or «cultic» homosexuality exists sometimes as part of initiation rites at which the young man symbolically receives the virile strength of the older warrior by means of a sexual contact. In some ancient Greek tribes boys acquired the status of women because they were cheaper to buy than a woman, but as woman-substitutes they had to do the hard labor on the fields (Freund, 1963). Socarides (1976) cites the historian Karlen who affirms that «No society has accepted preferential homosexuality. Nowhere is homosexuality or bisexuality a desired end in itself. Nowhere do parents say ‘It is all the same to me if my child is heterosexual or homosexual.'» Some cultures have institutionalized some form of homosexuality, but nearly always as something exceptional. Hence it is more appropriate to look at this institutionalized homosexuality as, perhaps historically grown, aberrations rather than manifestations of a universal and biologically normal human instinct. That some kind of institutionalized prostitution is accepted in our society, for instance, does not justify the inference that prostitution is viewed by the majority as normal, or natural, or healthy.

It is not correct to blame the Bible for the so-called culturally determined objections of Western society to homosexuality. Already the old Egyptians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Greeks did not accept it as normal; witness the studies of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and the socalled Mid-Assyrian Laws (Douma, 1973). As for the ancient Greeks, their supposed passion for homosexuality, which in the first place was more a type of pedophilia and ephebophilia (love for adolescents and maturing young men) than homosexuality in the broader sense of the word, was not a general phenomenon; witness the popular satires on homosexuals in the comedies of Aristophanes and the laws against homosexuality in Sparta and Athens, approved (in Athens) by a majority of the representatives of the bourgeoisie exactly in the period that homosexual pederasty would have been so «normal» and well-accepted (Flacelière, 1960; see also Opler, 1965).

A certain aversion to homosexuality is not to be understood as the product of cultural conditioning; it is much more likely a spontaneous, innate reaction of man’s healthy emotionality. We may perhaps be impressed by the enlightened idea that such feelings of disgust (and, for the homosexual himself who gives in to his urge, shame) should be discarded as learned inhibitions, but the case for their innate character is in fact much stronger. Is it not true as well that in our time we are inclined to repress from our awareness various feelings which are of themselves «instinctual» or natural, such as certain feelings of shame in relation to sexuality and feelings of aversion to unnatural sex behavior?

In all sorts of civilizations we see that the majority express this homosexuality-aversion (called «homophobia» by the advocates of homosexuality, in an attempt to associate it with «lack of freedom from old-fashioned beliefs»). That minorities were involved in and praised homosexual activities does not refute that the majority considered them sick, or decadent (Siegmund, 1973). At any rate, it is not correct that this aversion is a Christian by-product. When we learn how harshly Islamic peoples punish homosexual behavior, it may dawn upon us that there is more truth in the idea that Christianity has created the most balanced view on this orientation: disapproving of it, but at the same time approaching the individual homosexual as a fellow-human who needs healthy guidance. Primitive expressions of homosexuality-aversion such as occur in Communist China (Ruo-Wai Lg, 1975) are unimaginable in a society ruled by Christian principles. Returning to the Bible, it is true that its condemnations of homosexual behavior have inspired some religious fanatics to preach and practice persecutions of homosexuals, and many homosexuals were executed in the tragic episode of Calvinist rigor in Holland in 1770-32. Undeniably, the biblical admonitions against homosexuality have been used to strengthen already existing feelings of disapproval and contempt for homosexuals and many homosexuals have suffered from deep feelings of guilt and worthlessness because of such hostile interpretations. But then it is still not right to see the entire Christian history as an uninterrupted series of pogroms of homosexuals (Bailey, 1955), for homosexuality has been tolerated more or less in the same way as prostitution; for instance Pope Leo IX and the Council of Paris (1202) propagated quite a different and more human and understanding attitude.

To sum up, endocrinological and genetic research failed to substantiate the theory of a constitutional endowment. Not even a physical or physiological predisposing factor has been demonstrated, as had been postulated by Freud. So who can rationally insist that homosexuality would be a normal variant of human sexuality?[14]

But if it is a disturbance, theoretically it might be a physical or psychic one, or a mixture of both. However, in the absence of indications of a physical explanation (like a hormonal dysfunction or a somatic disease, we must turn to the psychological facts in order to see what light they can shed on the problem. In this book I shall focus on one of those psychological facts I regard as central for the understanding of homosexuality, viz. the homosexuality-associated neurotic self-pity. Before studying how this neurotic self-pity is related to the homosexual wish itself, we must learn to know the general behaviors of this neurotic self-pity, the way it comes into being, and its rules.

3. The «Self-Pitving Child» in the Neurotic; the Autopsychodrama, its Ongin and Fixation

In those homosexuals I analyzed or studied until now, I could observe the functioning of a psychic structure that had been described for the first time by Arndt (1950, 1955, 1958, 1962, 1967) under the name of autopsychodrama or autonomic psychic structure with a dramatic content.[15] Initially Arndt detected this dynamic structure in the mind of persons suffering from general neurotic affections and complexes of inferiority, but in the course of time it became clear to him that it operated as well in the mind of many homosexuals (Arndt, 1961). In my opinion, his observations may be generalized; I could observe this complex in Dutch, English, German, American, and Brazilian homosexuals coming from different cultural backgrounds. One can readily diagnose it in most welldocumented biographies of famous homosexuals like Oscar Wilde, Proust (Maurois, 1962), and Gide (van den Aardweg, 1967).

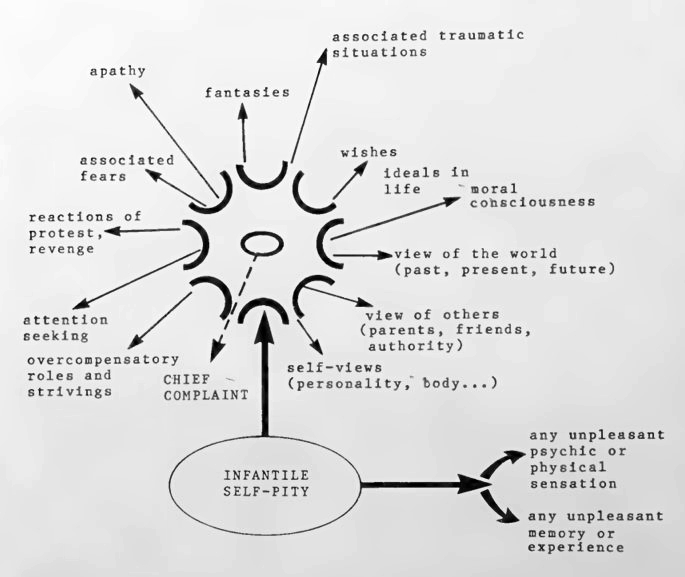

Autopsychodrama means infantile self-pity turned autonomous. A child or adolescent who experienced intense self-pity during a longer period of time usually does not get rid of it any more; it becomes firmly fixated in his mind, leading a life of its own, independent of the person’s further experiences or circumstances of life. This infantile self-pity recurs time and again, both with and without an external motive. We can best represent this structure as some closed circuit in the brain, acting spontaneously, emitting impulses (of self-pity) on its own initiative, and remaining unaltered during a lifetime. This infantile self-pity, which does not change in intensity or in form, is always active as an emotional force that influences a person’s sentiments, thoughts, and self-consciousness — and, in this way, his actions and reactions. The person who is subjected to an autopsychodrama feels, thinks, and acts partly as a self-pitying child, i.e., exactly as the child-with-intense-self-pity that he was in his past. Therefore we can also use the expression «the self-pitying child in the adult,» resulting in a double personality, the adult ego with his will, thoughts and feelings, plans and actions, and this self-pitying child. An alternative definition of the autopsychodrama is the «compulsion to indulge in feelings of infantile self-pity,» or the «compulsion to complain.» This dynamism, which appears to be fundamental in many neuroses, throws a new light on the genesis, structure and functioning of homosexuality in its various forms and degrees. For this reason it would be more adequate to speak of the «homosexual neurosis» than of «homosexuality,» and thus to link this particular neurosis to the other members of the extensive family of human neuroses (obsessive-compulsive neurosis, anxiety neurosis, hysteria, etc.), emphasizing that the similarities between homosexuality and other neuroses are far more essential than the differences.

Let us first describe the processes leading to the autonomization of infantile self-pity in neurosis and the general laws by which it is controlled before we deal with the question of the specific elements of the autopsychodrama of homosexual persons.

The infantile self-pity that eventually becomes fixated as a neurosis or autopsychodrama is a reaction to psychotraumatization; maybe it is the principal reaction to it, but it is certainly highly frequent in childhood. In spite of some interesting publications on the affect of grief (Landauer, 1925; Petö, 1946; Plessner, 1953; Averill, 1968), it has never had the scientific attention it deserves. Its relationship with human neuroses was never profoundly studied nor fully understood before the original observations and statements by Arndt.